As part of HSCTF, there was a reverse engineering problem entitled "λ1". The problem text was short and to the point "Here's the lock. Find the key." The first phrase "Here's the lock." linked to an archive containing three executables, one for each of the major operating systems. All three executables were 64-bit. This problem is the first of a series of reversing problems.

Ultimately, the goal of this problem was to retrieve the flag from one of the given executables. As a result, there's a wide assortment of approaches to this problem. I'm not going to go over all of them here because I certainly don't think I could produce all of them. Instead, I'm going to go over the approach that I anticipated as the most common solution to the problem. In fact, it's possible that this wasn't even the most common solution. Regardless, we'll carry forward.

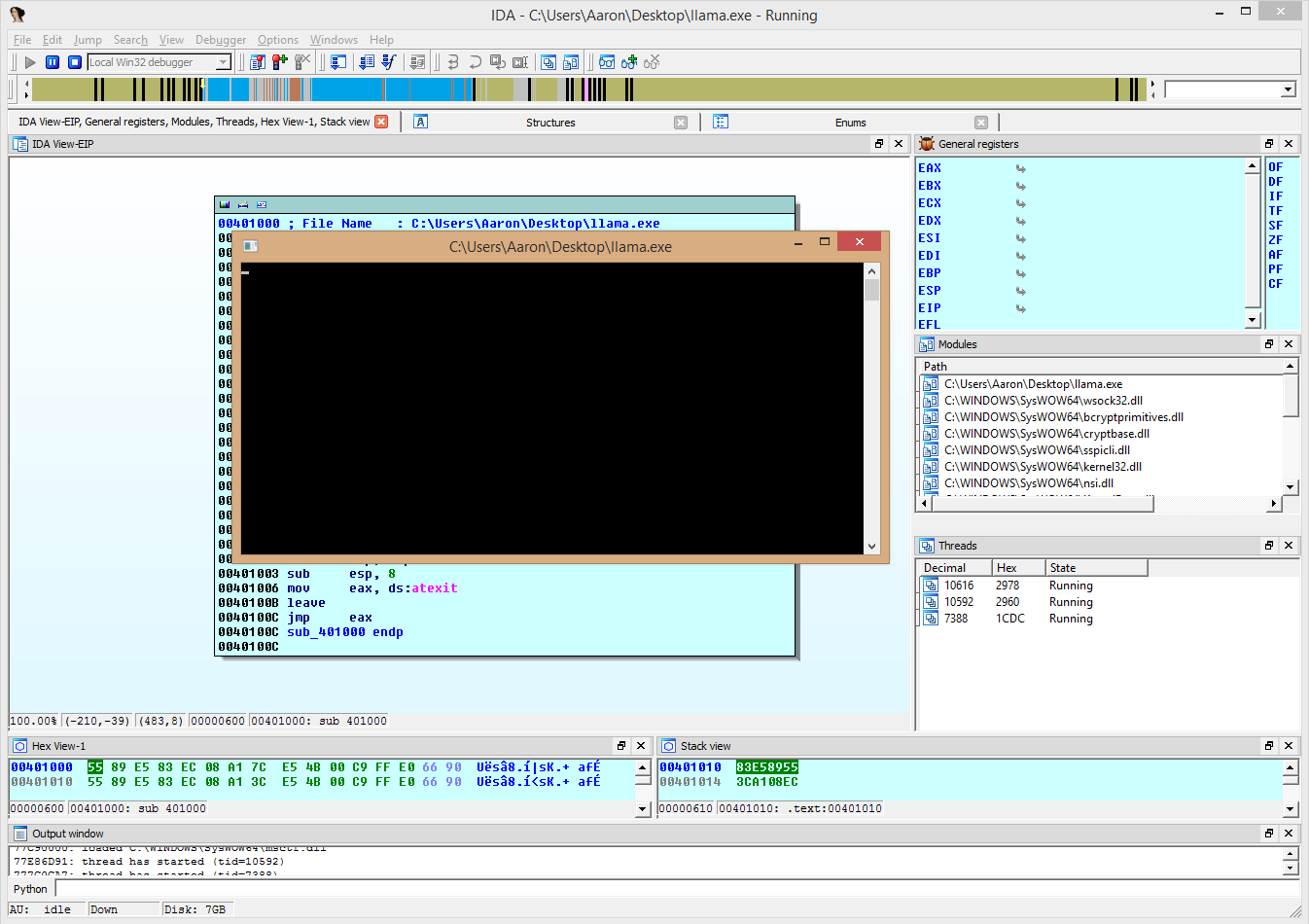

Recognizing that the problem is one of reverse engineering, my first reaction is to immediately fire up IDA. Upon attempting to open the executable, IDA fails to do so because of the lambda in the file name. So, I rename it to llama.exe and try again to open it. This time, it works out. Next, I will attempt to run the program.

Upon entering input, I notice that the program quickly ends, but I can catch that the output of the program depends on the value I input. I also notice that when I enter non-numbers, the program outputs a parsing error before exiting. Therefore, I can assume that the input needs to be a number. Since the output changes based on the input and there's no additional files included with these programs, I can assume that the information I'm looking for has to be stored in the executable in some form. So, let's look at the string table.

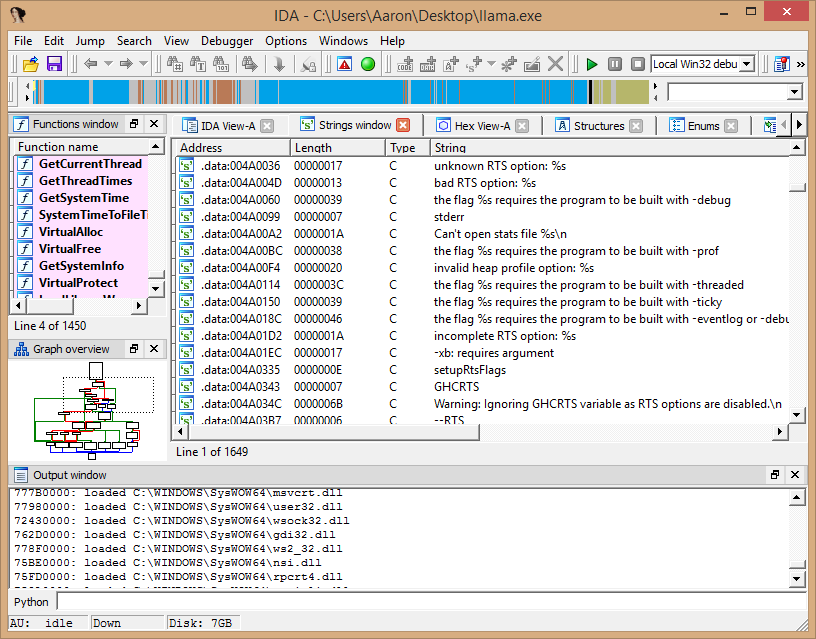

Well, what's this? It mentions GHC and RTS. If you didn't know what these things were, a quick search on DuckDuckGo will reveal that GHC is the primary Haskell compiler and that the RTS is the Haskell runtime. Therefore, we now know that this is a Haskell executable made with GHC. As a result, we also know that the .data section is entirely runtime related data and that .rodata is going to hold actual variables from our program. After all, Haskell is an immutable language and as a result, data is read-only. So, let's pull that up.

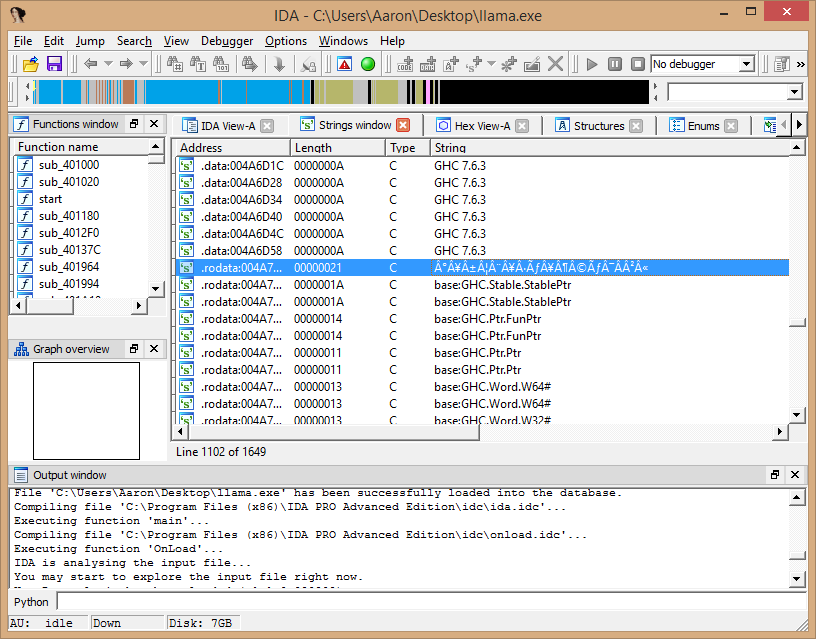

As it turns out, the first string in .rodata is a suspicious looking string and everything that follows it is denoted as being part of the base Haskell package. From this, we can infer that Haskell includes constants from the actual software as the first entry and then follows it with other strings from within Prelude. So, now, we need to figure out what to do with this string we found. Here it is: °¥±¦¨¥·Ã¥¶©Ã¯Â²«.

Judging from some of the previous problems in HSCTF and the fact that the majority of the string consists of accented capital A characters, my first guess would be that it's a Caesar cipher. After all, this suggests that there's a pretty tight grouping in values. So, we're going to have to build some sort of Caesar cipher solver to attempt this approach.

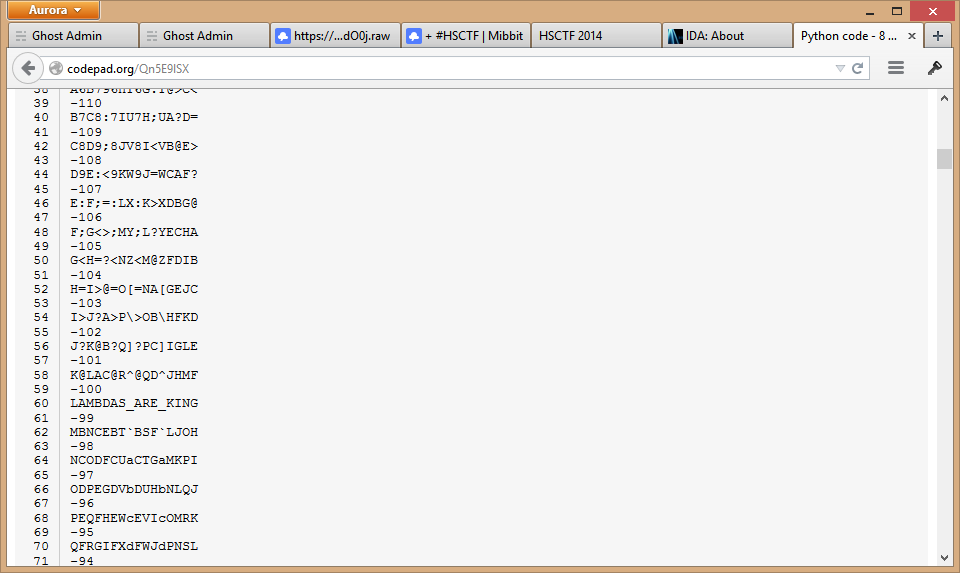

Here's our Python script:

def shifter(s):

for i in range(-129,128):

try:

print(i)

print(lambda z,y: "".join(map(lambda x:chr((ord(x)+y)%256),z)))(s,i)

except:

pass

shifter("\xb0\xa5\xb1\xa6\xa8\xa5\xb7\xc3\xa5\xb6\xa9\xc3\xaf\xad\xb2\xab")The script works by going over all possible shifts within a byte and outputting our input string shifted by each amount. For the actual input, you'll see that we had to use an ASCII table to convert the string into a format that Python could handle. This step may be optional depending on the language used for this part of the problem. Once this is done, let's explore the output.

Well, look at that. We searched through the input a little and we found something very, very suspicious. This string, LAMBDAS_ARE_KING, looks like it could be the key. In fact, it is indeed the key. We did it!